- Home

- /

- Uncategorized

- /

- Sex, suicide, silence

Sex, suicide, silence

By guest contributor Dr Analosa Veukiso-Ulugia

We’ve had a couple of suicides in the last couple of months by young Pacific youth and the rates for suicide are slowly increasing… and for one of our dads that I spoke to actually, he actually said to me prior to coming to the (teen parenting) programme because of the impact that his partner was hapu – he got her pregnant – he was so afraid that if his parents knew um, that he would be abandoned, like rejected. And that thought in his head just made him very depressed to the point that he nearly took his life, nearly took his life. – Key informant

In an ideal world, we would like to believe that this young man possessed the courage and confidence to approach his parents, and that he knew, regardless of his actions and ‘normal’ parental reaction, that ultimately he would be held in an environment of love and understanding. Sadly, this is not the case for many of our Pacific young people.

Analosa’s PhD research

This reality and many of the tensions Pacific young people face was relayed by one of eight experts who were involved in a study exploring the sexual health attitudes, knowledge and behaviour of Sāmoan youth in Aotearoa. We know that New Zealand’s rates of teen pregnancies are amongst the highest in the world. We know that Pacific and Maori populations feature disproportionately in terms of teenage birth rates and STIs such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea. We know that while condoms and contraception are available, they aren’t being used as effectively as possible. We know that more needs to be done to improve sexual health in our communities. The question is how? In addition to the eight experts involved in this study, information from 535 Sāmoan students across New Zealand involved in the Youth ‘07 health survey were reviewed, and eight focus groups involving 55 Auckland Sāmoan secondary school students were undertaken.

The key findings reinforce what we currently know about tackling difficult issues; in this case addressing sexual health issues for Sāmoans requires an understanding of context, the importance of communication, and the need for co-ordinated and responsive services. These findings may extend to other Pacific groups.

What is positive is that the young people involved in this study affirmed the importance of family and reported good relationships with their parents. Many shared their own accounts of the sacrifices their parents made in order for them to have a good education. However, most of the young people and experts shared that sex is something Pacific young people are not encouraged to talk about with their parents. This ‘silence’ is often linked to their parents’ cultural and religious values that frame how sexuality, fertility and pregnancy are understood, let alone discussed. Sex for some Pacific communities is often regarded as tapu or sacred. Cultural values such as respect, humility and servitude and the unique ways of relating within families and villages influence relationships and how issues are discussed.

It hugely is still a taboo subject. Don’t even go there, or don’t even talk about it. Because we have this what we call an ava fatafata (respecting boundaries, respecting hierarchical relationships), you know, with our brothers or our dads, you know, that the girls are not to talk about sex or any part of your body in front of your brother or in front of your dad, you know, it’s a form of disrespect. And so when the subject comes up it’s like you just do not go there, and so it’s never been there with our people.” – Key informant

The cost of staying silent?

However, are we prepared for the cost of staying silent? Of maintaining ‘respect’? The kind of respect where our young people feel they can’t approach us and learn ways of navigating difficult experiences in their relationships? Where they avoid seeking support from sexual health services due to fear that they would be seen by someone connected to their family or church? Fear that manifests, potentially triggering suicidal thoughts or harmful actions?

What emerges from this research is that communication, particularly communication patterns in families, is a critical area that we need to address. These findings echo the calls for public health efforts to focus on strengthening parent-children communication. However, a crucial element is appreciating how social and cultural conventions shape attitudes such as those regarding sex. As a researcher and a mother, it was encouraging to learn that while it was a small group, Pacific youth shared their mothers were starting to have discussions about sex with them.

Solutions

I’ve been asked, how can we bridge the gap that exists between generations around taboo subjects like sexual health, suicide and addiction? While there are many possible answers, in wearing my policy hat I maintain that we need coordinated and responsive interventions. The investment in Pacific and sexual health in the last few decades has given rise to a growing cultural resource in terms of knowledge and practice. We have leaders paving the way in Pacific sexual health and addressing communication within Pacific families. Village Collective and SWIPIC (South Waikato Pacific Islands Community Services) are our only Pacific sexual health promotion services in New Zealand, and they work tirelessly to equip our young people, families and communities with the right knowledge and resources. We have Pacific experts writing on these matters such as Sarah Brown-Ah Kau (2016), Dr Seini Taufa (2015), Amio Matenga-Ikihele (2012), Dr Fuafiva Fa’alau (2011), Dr Teuila Percival (2010), Nancy Naea (2008), Judy Matai’a (2006), Dr Anne Marie Tupuola (2000) and Associate Professor Melanie Anae and the Pacific Health Research Centre team (2000). What can we learn from our Pacific families who are talking about sex and relationships? What has helped them navigate these turbulent issues? In addition to good research that tells us how we are faring, we can learn much from these families and these thought leaders.

You can’t change something until you acknowledge it exists

As wife to a very handsome Tongan, Peter Veukiso, mother to Paula (aged 7) and Michael (aged 5), and daughter to Malia Paula Ulugia, openly communicating about sex and relationships has been a tenuous journey. Pete’s experience as a Police officer and mine as a social worker has influenced our understanding of sexual issues, and united us in our goal as parents. Peter and I have openly encouraged Paula and Michael to name their penis and vagina. However, before we could teach them the basics of sexual safety, we needed to be comfortable with the subject ourselves. We have had to ask each other the hard questions: how were we raised? Did we agree on how we would raise our children? What values do we want to impart to them? We have accepted that we are raising our children in a slightly different way to how we were raised. However, like our parents, we are united in the end goal: we want our children to develop into well-rounded, confident, healthy individuals who respect themselves, God and others.

Going forward

I would like to thank Le Va and those who have provided an opportunity to share some of the realities facing our young people. Thank you for your courage in acknowledging the significance of this research, and that these issues affect all of society – our Pacific young people, parents, families, schools, health and social service providers and policy agents.

It’s possible that communication patterns in Pacific families, particularly around sex, may change given the changing social and demographic profile. We know that a large number of our Pacific children are born in New Zealand, and are also exposed to sexual health lessons in their school. However, I’m not prepared to leave an improvement in communication to chance, therefore I’m doing my part as a wife, mother, family member and lecturer – my question is – are you doing yours?

About the author: Analosa Veukiso-Ulugia

About the author: Analosa Veukiso-Ulugia

Analosa Veukiso-Ulugia is a Sāmoan lecturer in the School of Counselling, Human Services and Social Work, in the Faculty of Education and Social Work, at the University of Auckland. A health professional specialising in Pacific youth health, Analosa is committed to the empowerment of Pacific women and young people, specifically in the area of sexual and mental health.

Analosa draws on over 15 years’ of clinical, community, research and management experience, with her previous roles including the following.

- Manager, Pacific Non-Regulated Health Workforce Study with Ministry of Health and Health Research Council of New Zealand.

- Adolescent Health Social Worker with Counties Manukau Health.

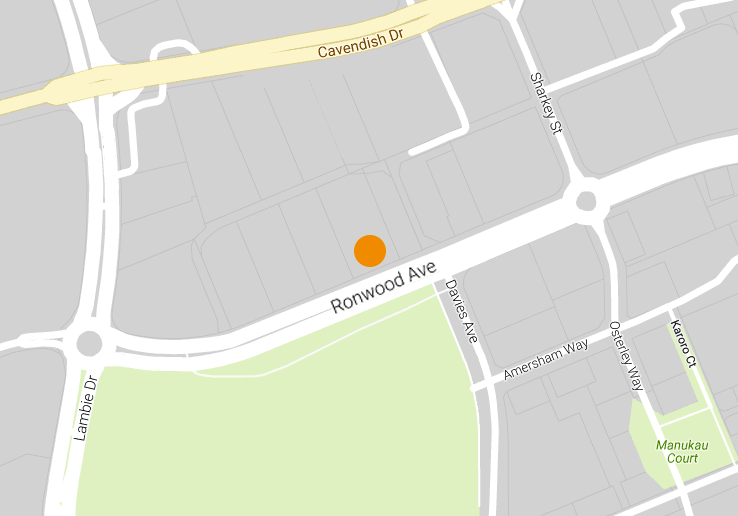

- Social Worker with Oranga Tamariki (Care and Protection and Youth Justice).

Analosa’s PhD study was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand through a Pacific Career Development Award.